GARY LEONARD

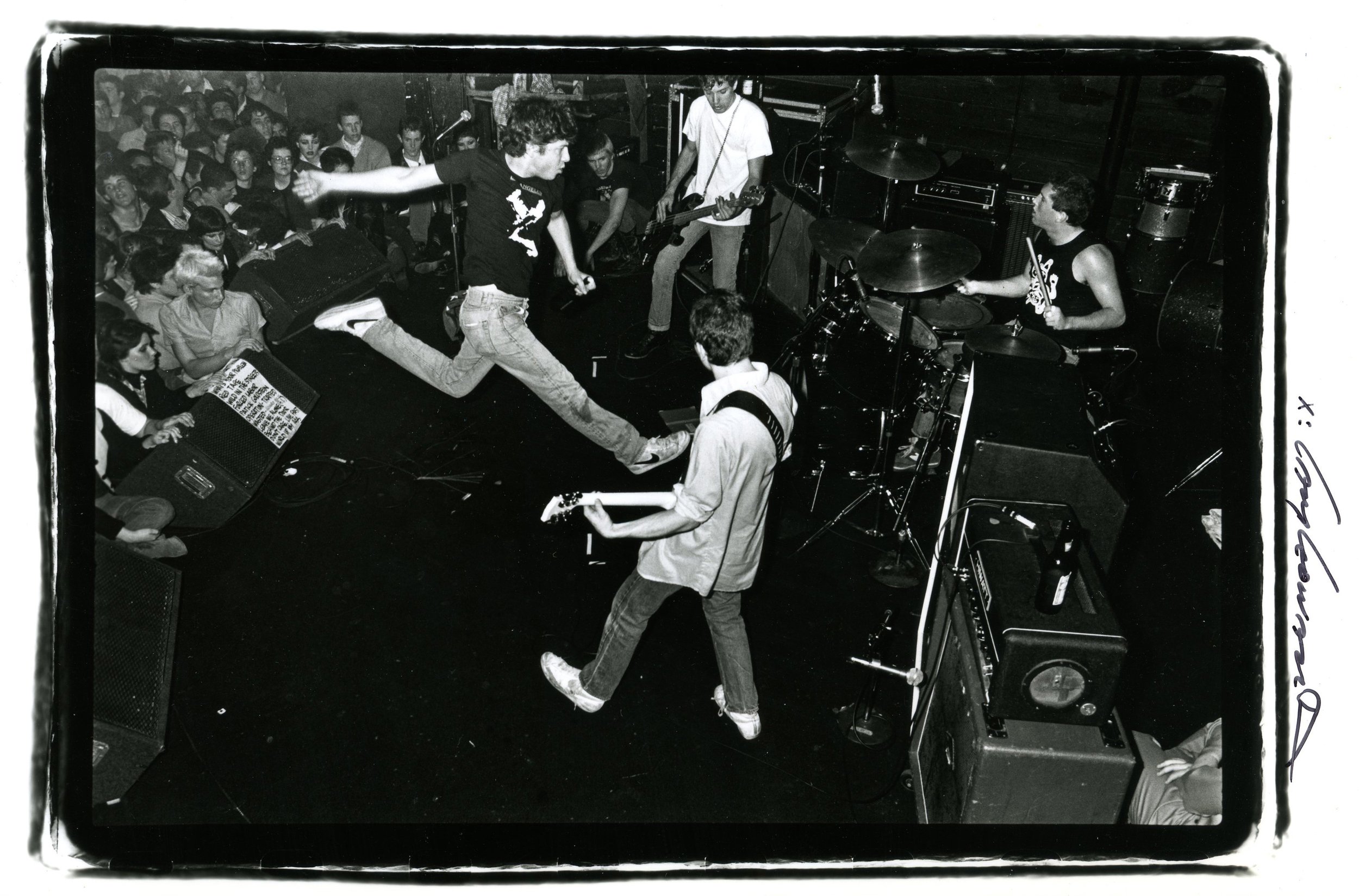

Circle Jerks at the Starwood, 1981

I met Gary outside the historic, classical and opulent Walter P. Story high-rise in downtown Los Angeles, and he immediately snapped my photo. Riding the elevator, he explained Story and his wife used to live in the penthouse of the old building, another wealthy businessman who’d made his way west to California to live the dream.

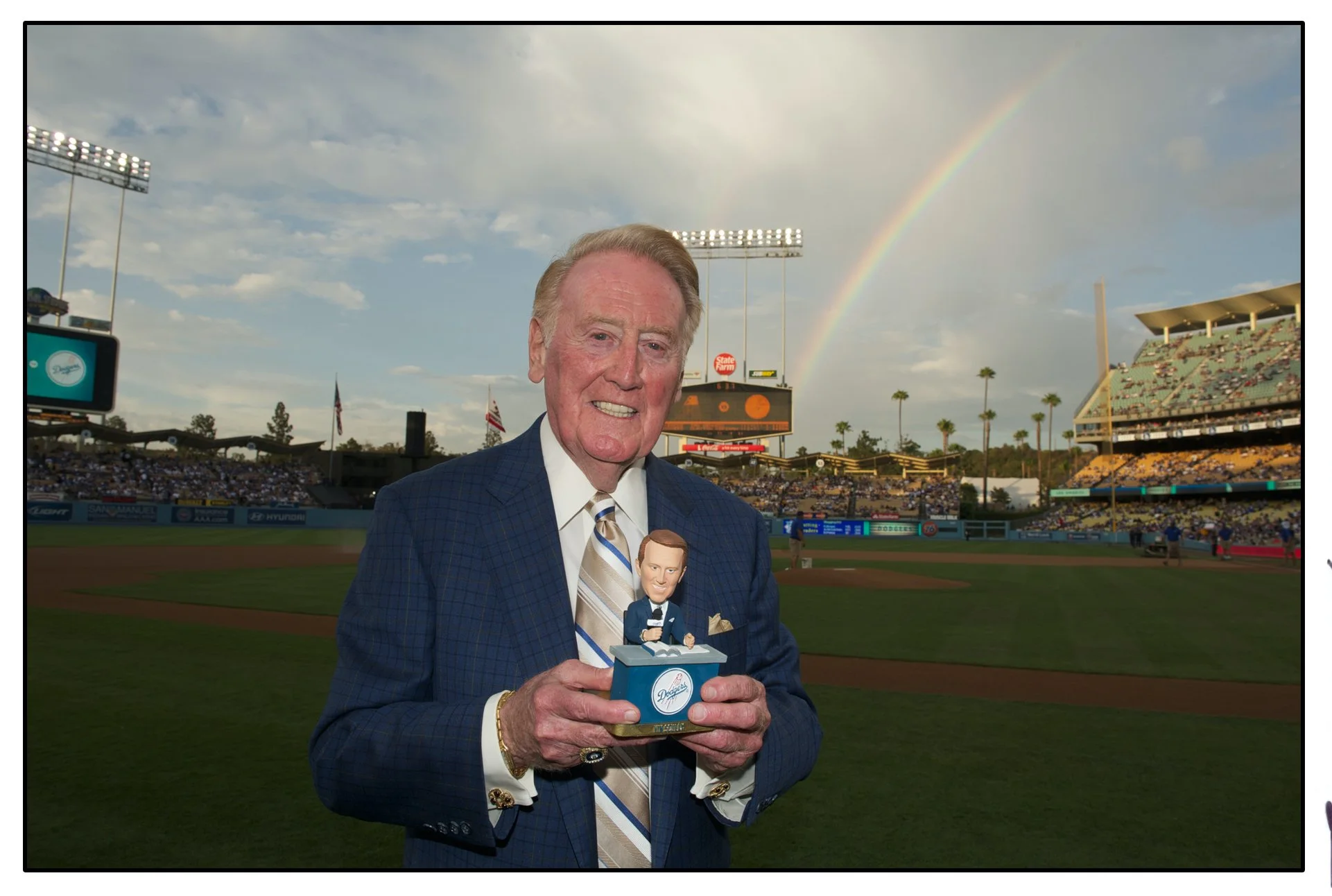

A witness to many generations of Los Angeles, Gary is one of our coolest elders, a keeper of memories, a time traveler, and an artist who’s been documenting this city in his own way since he was a child. His curiosity in capturing Los Angeles in time and space is devoted and we’re a better city with Gary on the streets, a chronicler of Angeleno culture, snapping away at everyone and everything. Not to mention, sweet gigs like watching Gehry and the many strong and sensible workers create the Walt Disney Concert Hall from the dirt up (get yourself a copy of his Symphony in Steel: Walt Disney Concert Hall Goes Up book ). A long-time Dodgers fan, he’s seen the stadium since its infancy and given us beloved images of Vin Scully and the boys in blue. The first I knew of his photos were the epic black and white shots of the Go-Go’s from their Hollywood days, but I’m honestly skimming off the top with these terrific examples. Gary has an epic archive, and I’d bet that he may very well be snapping a photo right now, as I type this and as you read our lovely conversation.

TRINA: What was it like growing up in the San Fernando Valley?

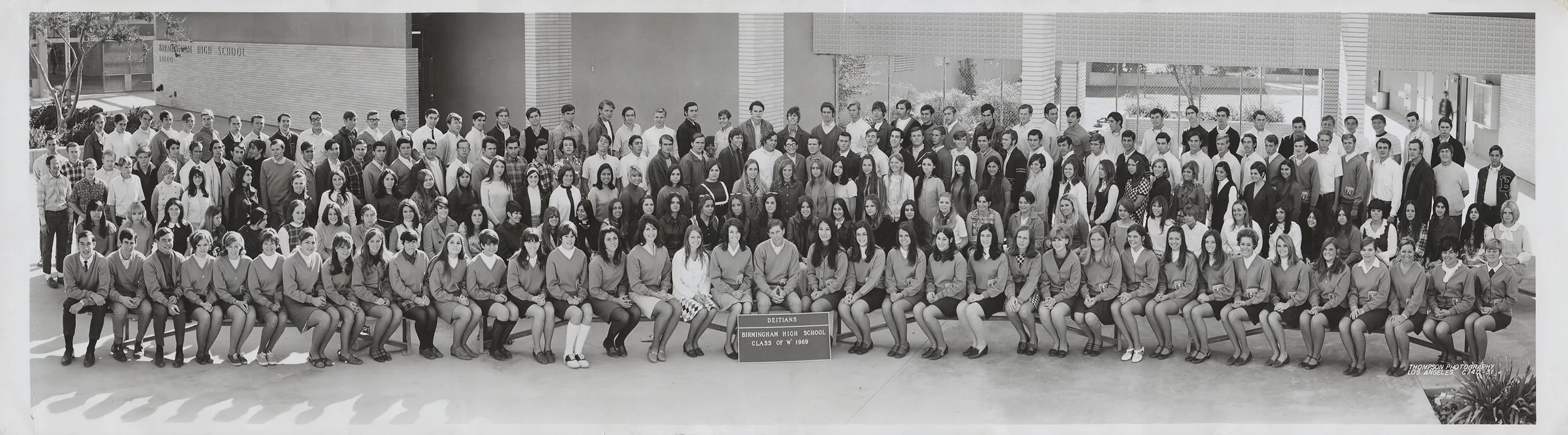

GARY: I absolutely love the Valley. I love where I came from. When I was in first grade Gary was a popular name. I think it was [because of] Gary Cooper, because it's a name that came after World War II, when I was in kindergarten, which was somewhere around 1954 - 55. There were five Gary's in my class. Gary Wilson, Gary Weisberg, Gary Hamilton, Gary Lee Luckenbacker, and myself. And in 12th grade there were still four of 'em. Gary Lee Luckenbecker didn't make it. But everybody else did, we went to Birmingham High School.

Birmingham High School had been an army hospital during World War II. The Valley was growing so quick. They had built Reseda High School and the new high school, for the Valley, which was growing. There were too many people coming in, so they took the Army Hospital, which they had built for the veterans, and by 1952, it had been decommissioned. It looks like it is barracks, and they made it into a junior and senior high school.

TRINA: Did you feel like you had to do something to stand out since there were so many Gary's?

GARY: In my 12th grade picture, I'm in it twice.

TRINA: Really?

Gary’s High School Senior Class photo, 1969

GARY: Yeah. I went to Portola Junior High School, which was in Tarzana. In the ninth grade, we had a senior picture, and if you're familiar with senior photos, they're long and they're basically contact prints of a very large negative. You have a lens, and if you get even the widest angle, I've got to get so far back that it's wasted space. At some point, and they're probably very old, because you see on panorama cameras, you were able to get up close and had a lens. The group would wrap around the camera, and the lens would go from, ‘Hold, very still, everybody hold very still.’ I saw that in ninth grade and promised myself that in 12th grade when they did it again, that I would get on one side and go to the other. So, when you ask about standing out in your class, I stand out more than anybody else in the whole class.

TRINA: Like, literally.

GARY: Literally in the whole class. There were five Gary's, but my father was a doctor. My father was an obstetrician. He came from the East Coast to the Valley because it was the post-World War II American Dream. I'm sure there were other cities, but you really felt that, at least I did, there. Until I was three, we lived in Van Nuys and then we moved because he was doing better. We moved to the hills of Encino into what was kind of a tract. Not a tract house, but you had houses that were on lots with a backyard and small ranch style house. In my class, they'd say, ‘What did your father do?’ It's amazing that, all these years later, I remember there were five Gary’s, and I remember that every other person's father was a developer.

TRINA: Oh my.

GARY: God. Every one. It was just, ‘My name's so and so, and my father's a developer.’ They came to me and, ‘My father's a doctor,’ and they came to somebody else and then the next one, ‘I'm so and so, and my father's a developer,’ and ‘My father's a developer.’ Now it makes perfect sense.

TRINA: Sure does.

GARY: Now that's pretty wild. As I connected with the city and wanted to know more and more about where the city comes from, as I've dug to know about the first Spanish expedition. The first, Father Crespi accompanied Portola in 1769. They came to the LA River. It was August. It used to be fresher, all the different dates, but luckily Crespi just wrote all this stuff down. It's the first documentation in English. I'd like to get a lot more of what came before, but it's not written.

But then it occurred to me, I've discovered the whole history of the city from developers. Walter P. Story.

TRINA: Of course.

GARY: Walter P. Story. The King of Spain was a developer that started with Crespi, like ‘Okay. The Valley looks good. They've got oak trees.’

TRINA: They could have just named their development company Manifest Destiny.

GARY: Right. Yeah, that’s just it. Since I was a little kid, the first thing you're attracted to, I think, is Hollywood. I think the first thing you begin to have a romantic notion about, and particularly in Encino where I've come to learn later, we were kind of late. It was bought in 1913 as a full Rancho, a square going from Sepulveda to Lindley, I think, and then Victory and Mulholland Drive. It was a small rancho; the rest of the ranchos were much larger. But it sold in 1913 to a fellow named W. H. Hay, Hayvenhurst, they changed the name. There's Hayvenhurst, the Garden of Allah. You ever heard of the Garden of Allah, Crescent Heights and Sunset?

TRINA: Oh, yeah.

GARY: It was originally Hayvenhurst, Hay’s Estate, because first he developed it. They'd move around…so I began to change. Clark Gable doesn't connect to the real city. He connects to some studio. If you go into the studio where movies were made, then you can kind of connect to the guy who was in the film. But the real romance is with the developers. The real romance with the city and the history of the city are the guys who came. There are some good developers and then there's Jeffrey Palmer. Do you know Jeffrey?

TRINA: No.

GARY: You know all the places around the freeway? You know all the apartments when you go to the interchange?

TRINA: Yeah.

GARY: All the apartments, those are Jeffrey Palmer.

TRINA: Oh, he’s the one that lit his on fire.

GARY: Yes.

TRINA: The Orsini.

GARY: Yes. He's despised, because he builds to code so there's no zoning changes that he needs, but he just builds the same thing. Everywhere. He's literally on the freeway. You can step outside your apartment, but you never see anybody step out of their apartment. The patio is right on the freeway.

TRINA: Every inch of space you could develop. That’s pretty crazy.

GARY: Yeah. The Valley was that. I felt the Old West. I have come to understand what I felt in studying the history that there was a connection because, I just sensed it. We lived up Hayvenhurst Avenue which now goes all the way to Mulholland. We lived not too far up, and it didn't go through. There were no freeways. The freeways came relatively fast, in 1960. I was nine years old.

TRINA: Did you ride a bike?

GARY: I did have a bicycle and ride all over the place and hiked everywhere. When you're nine years old, it’s a long time and you remember. Now it's ugly, but you remember the orange groves, and you make that connection. I didn't know what the freeways were going to do. I remember when they opened the 101, the Ventura Freeway.

So, when you asked, what was it like? It was idyllic. The fact is that a lot of kids I knew, [their] parents were in the film business. They weren't necessarily movie stars. Some of them are big names, but they lead an orchestra, or they were in lighting, or they were in cinematography. But there were stars. Clark Gable, I mentioned his name, lived down the street. John Wayne. The list is relatively long 'cause it was marketed as five acre estates to movie people. I've come to understand that. You had that sense that as you watched TV, that we were shaping the nation and it was all coming from the Valley. That connection, the fact that everybody watched TV and there were only so few channels, there was a certain commonality. That's what's been lost. Now we're all looking with our devices at different channels.

TRINA: Yeah.

GARY: But back then when, I'm trying to think of some TV show that I knew someone was working on, and a relative back east, you know, is watching that same show. I kind of have a connection to people who are doing it. Growing up in the Valley, you had that sense, I had that sense. But I'm not sure everybody had it. But I made a big connection to the history to the city, and my dad had a dark room.

TRINA: Ahh.

GARY: If you were affluent, and he was, it was kind of upper middle class, he had some time on his hands and doctors always had good cameras.

TRINA: It was like a hobby for him.

GARY: Yeah. He had a lot of hobbies.

TRINA: This is how you were introduced to photography?

GARY: What comes to mind is walking in the dark room once opening the door. Have you ever used a dark room?

TRINA: Yes. I studied photography and still shoot film. I have two 35mm SLR cameras.

GARY: Cameras. I donate time to the Silver Lake Conservatory of Music. That's a real community. It's like a church; you see these kids grow up and the way they develop.

I'm [there] talking, kids are interested in what I do, and I'm having this conversation with someone who might be. I talk about film, and they didn't say anything. Right. And I go, ‘Do you know what film is? Have you ever seen it?’ And I realized because they've expressed an interest in knowing photography, I'll go bring some film.

TRINA: Nice.

GARY: ‘Here's what film is, here's loading it.’

TRINA: ‘This is how to load a camera.’

GARY: Now, ever since then, everybody's younger than I am now, that's why I have to ask. Okay, so you know what a dark room is. My dad had a dark room. I walked in and opened the door, and I did it once.

TRINA: Did he get mad?

GARY: Well, sure. I was like, ‘Whatcha doing?’ Yeah. It all got exposed and, and I never did it again. The second lesson was sitting at the chemistry watching the images come up.

TRINA: How old were you?

GARY: Probably four or five. He gave me a camera; it must have been seven or eight. All the the photographs were of, and I still have them, family at the house. But the first time I ever took it out was the Dodger photo day at the Coliseum. I made this connection 'cause they would have the news on in the morning, whether I listened or not, I did get City Council and the Dodgers. There are names of old politicians and old councilmen, who I got to meet later, who actually brought the Dodgers [to Los Angeles].

That was my first experience. We went to the Coliseum for Dodger photo day. It was 1960 because on the side of the photos, it says 19 19 60. I took pictures of Duke Snider at the Coliseum. They played there four years.

TRINA: Before the stadium.

GARY: Right. They came in 1958. They came in last place. They won the World Series in 1959 and in 1959. I'm getting goosebumps.

TRINA: Totally. Me too. I went to the World Series.

GARY: Vin Scully.

He motions to a large box on a shelf in his archives, which dominate the room analog style. Just rows of shelves with boxes…

Vin Scully, Dodgers Stadium

GARY: You see a box over there? Yeah. Vin Scully stuff. I got to listen to the games. My parents went. I probably went in 1959. I remember a game where Sandy Koufax, who became a great pitcher, it was so wonderful that I got to see him when he was wild. I don't hear anybody tell those stories. He walked the first three batters and then gave up a home run. And they pulled him. I'm sure we waited a few innings, but it seemed like my dad picked us up and we drove home. He used to get frustrated.

TRINA: Yeah.

GARY: The thing about Dodgers games is everybody leaves early.

TRINA: Oh god. It's so bad. Yeah. Well, now it's 'cause of the traffic.

GARY: Also, it was traffic, even back then.

TRINA: So funny. So, you had the bug; you had a camera. Did you kind of already have an inkling and know that you were going to be a photographer?

GARY: I made a connection. All the memories are not accurate, but the memory is, I was driving home from the Dodger game, and I had this epiphany. The only way to tell you about that is, I stuck the camera out and just pressed the button. That I had this, ‘It can be not stand somebody up, go to Dodger photo day, and here, I'll take your picture.’ It could be something else. And that held. It's pictures of leaves that we were driving by. I still have the photo. It's all in here.

TRINA: You saw the art. It's like, you could tell.

GARY: I made this connection to it. That picture in high school in 12th grade I took, I was in it, but I took it.

TRINA: Were you like in the photo club? Working on the newspaper?

GARY: I never really worked on the newspapers till I got to college. We had photo books all over the house. That was the thing. We had encyclopedias.

TRINA: Yeah. We used to have those National Geographic photo books.

Wilshire Grand, DTLA

GARY: Yes. And what'd your parents do?

TRINA: My parents were teachers.

GARY: My sister was on Jeopardy.

TRINA: Really? Smarty pants.

GARY: I'm the black sheep.

TRINA: Sure.

GARY: Everybody else went on in academics. My sister's a certified public accountant. I have another sister who's got multiple master’s degrees and my brother has a master’s in business. Yeah. I didn't fit. I was always in trouble. I wasn't a good student. I didn't take well to LAUSD.

TRINA: Yeah?

GARY: You were lucky because, I hear you went to a magnet.

TRINA: Well, I was a black sheep, but I figured out how to like, get good grades and cut school and still hang out with the cool kids. Since my parents were teachers, I had to figure out how to get the grades.

GARY: But you learned.

TRINA: Yeah, I did.

GARY: I couldn't keep up. They had a system. What I meant by magnets, at the time you went, they had already begun to address, we need more than one single classroom in one way for 35 students. I've discovered that if, I may be ADD, there may be some category, but it wasn't LAUSD. Once I fell behind, there's no catching up. It's still true. Someone will be explaining something to me, like the iPhone and I began to realize whatever condition I suffer from, I went to computer class, and they say, ‘You don't need to know anything.’ And he starts in; I raise my hand. ‘Tell me how to turn it on? Tell me where's the on button?’

By the time I got to high school, I was so afraid of not going to college that I figured out how to learn for exams. I had the average because I went to UCLA. UCLA now is hard to get into. [Back then ] you simply needed to be average, and you needed to have taken what they referred to as the A to F requirements. There was a catalog and there's A requirement, B requirement, C requirement and one additional year of math. Algebra and geometry. I actually liked geometry. That was the only class I actually learned something because it was graphics and there were compasses. I got the B average, they had to let me in. State schools back then had been designed so that they would be your local college. I paid more in books than I did for tuition.

TRINA: Did you study photography?

GARY: That's when I connected to art school.

TRINA: Thank goodness.

GARY: Yes. Slide after slide, photographer after photographer. I became this hybrid because I found the UCLA Daily Bruin. That’s where I connected with this is what I'm going to be doing. I call myself a hybrid 'cause I know all the artists and at the same time, I like having assignments. I like being out. They would have assignments on the wall, and I'd take them, and I also discovered there are all these amazing people who come to UCLA.

TRINA: Guests. Visitors.

GARY: Yes. I photographed Richard Nixon because I was from the UCLA Daily Bruin, and Leonid Brezhnev, the former Soviet Premier.

TRINA: Amazing. I had read that you were shooting from day one at the Walt Disney Concert Hall building project.

GARY: Yeah. History. Oh, look at this.

Gary shows me current photos in his camera from the LACMA David Geffen Galleries construction he is documenting.

GARY: What excites me now, well, this doesn't really put it on, but the building's done. The foreground will never…this looks relatively like it's going to look. This is a pretty good mess here.

He shares exterior shots of the massive construction of the new galleries in progress, in the dirt, with unfinished plumbing, and building materials stacked in piles. One is after the rain and features huge puddles in the foreground of the concrete building.

TRINA: It’s like from day one, watching something evolve. Do you have a process? Are you just kind of boots on the ground feeling it out?

GARY: It's really organic and it's wonderful. It's like being in heaven and only because, the light yesterday. The light in these photographs. There are hundreds of them because I make my rounds and almost every day, I'll, I'll find something. I was moved. What motivated me here to this kind of little niche is pictures of City Hall where you see the steel from 1928. I think it was done in 1929.

TRINA: It's the old architecture.

GARY: You can see it's the shape of City Hall, the symbol of the city that I'm really connected to. I mean, Dragnet and every badge, but I look at that photo, and I would go through my parents' photos and spend hours just wanting to go there. Like, is there a street sign? I evolved to a point where my places to photograph, [in] my time.

And this [LACMA DGG construction] picture will be looked at by that kid who's like me. And god, it's, it's brand new. I'm just shooting for myself, and I've evolved to the point where I get so excited. It's like, I'm time traveling. It's like, yes, there it is.

TRINA: What was it like watching the Walt Disney Center come to life in DTLA? That was so historical.

GARY: No one cared about Frank Geary.

TRINA: He's so cool.

GARY: They didn't care. He wasn't like the star that he is now. I first met Frank at my first project, the Children's Museum, where the Triforium is.

TRINA: The old Children's Museum?

GARY: Yes. You probably went there when you were a kid.

TRINA: I did. I loved that museum. It was so fun.

GARY: I met Frank in 1979. It was the first project that I documented the construction of, the Children's Museum that was happening inside that building next to the Triforium. I digress; this is a wonderful portrait.

Gary scrolls through more photos on his camera and shows me an image of construction workers he recently shot at LACMA DGG.

TRINA: Love that.

GARY: The people are really something. That is huge. I connect with the people. It was musicians, it is musicians, and then I came around because I do it as art. There’s Weegee, there’s Les Krims, there's all the people I saw in it but then there's this hybrid element of having loved working for the Bruin and loved being out all day every day. I stop for guests; I take pictures of the guests. The work's never been better.

He continues to look at his images he recently shot and shares more.

GARY: Oh, here's Jackie. Oh, this was yesterday. Jackie Goldberg is getting her Jackie Goldberg Square. Do you know Sunset Junction?

TRINA: Of course. I lived there for like 12 years, 13 years. I lived right by there.

GARY: There's amazing history there.

TRINA: Yeah. The Black Cat … and I was in the Manzanita Community Garden that goes down the steps right off Sunset.

Jackie Goldberg Square ceremony unveiling, 2025

GARY: Here.

He shows me an image of the newly commissioned Jackie Goldberg Square ceremony in Silver Lake at Sunset Junction.

Jackie Goldberg Square ceremony, 2025

TRINA: Wow. That’s where one of my favorite memories of Sunset Junction is. Remember the concert festival?

GARY: Yes.

TRINA: This reminds me, looking at that, of that last show that happened right there when Fishbone played and kids were climbing those lampposts and jumping from them right on there. Where the sign is. Go Jackie Goldberg!

GARY: It’s her district. After I go to LACMA, then there’s Jackie Goldberg. There’s every old leftie to Sheila Keel to all these guys, where I'm the young one.

TRINA: Do people call you and always invite you to come photograph or do you just know what's going on?

He laughs and shows me more images of Jackie Goldberg Square.

Jackie Goldberg Square ceremony, 2025

GARY: I'm showing you this because they unveiled the sign. They put it on five different corners. I went back the following day when they were actually putting up the signs. Here’s the street sign guys.

Jackie Goldberg Square sign crew, 2025

Jackie Goldberg Square sign install, 2025

Jackie Goldberg Square signs, 2025

TRINA: Wow.

GARY: I get to leave this stuff behind, you know? Someone might be interested sometime.

TRINA: People are. It’s the history of Los Angeles.

GARY: Here's the sign.

Jackie Goldberg Square at Sunset Junction, 2025

TRINA: The light was great.

GARY: It was perfect. Look at this.

He scrolls through his camera more and shows me a shot of a wall in DTLA with some graffiti that says, “Fuck Israel.”

TRINA: (laughing) Good lettering.

GARY: I had to stop for that. It’s weird. It says, ‘Fuck Israel.’ I’m Jewish.

TRINA: I don’ think fuck Israel necessarily means fuck Jews. That's for sure.

GARY: It shouldn’t. I don’t believe in god, but it’s weird when you’re Jewish. Because you’re still Jewish.

TRINA: Yeah, I’m a recovering Catholic. I don’t believe in god either.

GARY: Then you understand.

TRINA: Yep, it’s a strange world.

He continues to advance through his camera photos. There’s something he’s looking for…

GARY: I’m such a bad boy. Okay, here it is. I finally got to it.

Gary shows me pics of an event he shot at the Broad Museum.

GARY: Okay, here it is. I finally got to it here. That's Joanne Heiler. She's the director of the Broad. She spoke. Now the curator's up talking. She's looking at her iPhone.

TRINA: I see it. Yeah, I see her.

GARY: I don't know what's on her phone, but there. After that, I kind of saw, ‘Wait a minute, I can see her iPhone.’ I tilted the camera (laughs) so it's only her and the curator so that you can definitely see he's talking, but she's on her iPhone.

TRINA: She's just scrolling away.

GARY: That's what I look for at these.

TRINA: Public gatherings?

GARY: Yeah. I'm also recording Jackie [Goldberg]. She's my neighbor, and I like her in Berkeley in the sixties. But when I see that, well, I got to get that. That is our times.

TRINA: Yeah.

GARY: That is our times. I thought, yeah, that's it (laugh). That's it. It's the back of her and she’s scrolling art; she is scrolling art! She's scrolling at this public opening that she had just introduced everybody to and taken her seat. This is what was going on. It is the story right now.

TRINA: The world inside the screen. The world outside the screen. Okay, we do digress, but let’s go back a little bit. You were going to UCLA, would you say at that point you always had your camera with you?

GARY: Yeah. It really came together for me in college. I'd already been taking pictures in high school, junior high school. I wasn't taking my camera everywhere, but I was shooting. I knew I had an eye. I'd shoot around the neighborhood. Those pictures are wonderful. If I had a, well, everybody's got an iPhone, so everybody, everything's being recorded. But if I could go back, I'd photograph my friends more. I'd photograph high school more.

I just took your picture. I photograph the people who are around me and I photograph everything now.

TRINA: Yeah. I always wish I had more photos from junior high school. It was such a wild time, all the kids climbing on the buses doing graffiti. I do think about all the crazy stuff I wish I could’ve shot.

GARY: And I photographed presidents and what's precious that you don't realize going by is…

TRINA: The tree that you always saw in your neighborhood and one day its gone.

GARY: There was a lot of growing stuff. When I was 12 or 13, I went to a summer camp up north and met kids who lived in other parts of different places. I met someone who became a friend who lived in Palo Alto, and he invited me up in the off year. It was 1966 and I think it would've been around Thanksgiving.

I get off the plane, and he says, ‘We're going to Haight Ashbury.’ I went to San Francisco. I went a couple of years to that summer camp, and the counselors would go to San Francisco. I always had this sense of San Francisco; it was like New York. I hadn't been to New York either. It was just this romantic notion, this romantic sense of North Beach and a creative culture.

Same thing with New York, you don't know what it's like, but you imagine it. And particularly in New York where nobody drives.

TRINA: It's so crazy.

GARY: I had this romantic notion of San Francisco, this Haight Ashbury. There's this thing going on in Haight Ashbury and the way he described it, he mentioned head shops and there was one at the time called the Psychedelic Shop.

TRINA: Yep.

GARY: The way he described Haight Ashbury to me was that someone takes a parking meter, puts money in it, and then lies down in the spot. I didn't quite know what that meant. But we went to Haight Ashbury. I couldn't believe it, that there were so many human beings bustling and looking the way they did.

The Beatles were already happening. So long hair, but not like the long hair that I was used to. You know, real hippies. Hippies were only on Haight Ashbury. The other thing that he turned me onto, and this is the beginning of punk for me, is the history of popular radio. Kids radio was AM; all radio was AM until around 1966.

TRINA: Yeah, it all changed in San Francisco. Big Daddy, Tom Donahue. I do know the history; they had the first rock ‘n’ roll radio station.

GARY: FM was prior, 'cause every once in a while, I'd turn it on and it, it was music, maybe classical music. There were stations that if you were a kid, you didn't listen to. It was not anything that anyone you knew whether they were parents or young kids ever listened to. Although I do remember a friend of our family said this would've been earlier KPFK, which is still public radio.

TRINA: Yes.

GARY: KPFK, and we may have turned that on in our house, was left wing political freeform radio. But there wasn't music coming out of it. So that Thanksgiving my friend says, you've got to hear this. He puts on the first radio station that was, someone got the bright idea of going where no one else was going. We can't do it on AM, that's what everybody's listening to. We'll go to FM. It was this one person listens to it, two people listen to it, three people, where DJ’s get to play more than two-minute records. It just blew my mind. I think they played “Alice's Restaurant.”

TRINA: They definitely played “Alice's Restaurant.”

GARY: It was Thanksgiving, and it was 20 minutes. How?! I love “Alice’s Restaurant,” but it was also that, on pop radio you couldn't have a song longer than two minutes. I went back home. I was in junior high school still, about to graduate, and I said, ‘You can't believe what's going on in San Francisco.’ No one knew what I was talking about but by the spring of 1967, Life Mag.

TRINA: Life Magazine had that big article and they called him hippies.

GARY: God, you know.

TRINA: I do. I’ve met some of those folks who that started that radio station. Rachel Donahue, Kathy Lerner.

GARY: Okay. I was introduced to this idea as a 14, 15-year-old. I didn't have photography then…

TRINA: …In that way.

GARY: In that way. I did have my camera, but I shot my friends. I'm always getting better. I came back and sure enough, by the spring, everybody knew. The first radio station here was 106.7. I can't tell you when it migrated to Los Angeles, but it wasn't long after. They were related somehow.

TRINA: Oh, there’s the relationship to KROQ.

GARY: It wasn't KROQ. It was KPPC. Pasadena Presbyterian Church.

TRINA: (laughs) Really?

GARY: It was in the basement of the Pasadena Presbyterian Church, and it was called KPPC. I remember. Freeform radio, what made it special was that the DJ’s played whatever they wanted. It was programmed by the DJ’s. God, I used to wake up to it. It was just wonderful. Once everybody started listening to it, the DJ’s went on strike because they were making a lot of money, and it wasn't being spread around. So KPPC was replaced by KMET.

TRINA: I know KMET! They had a great logo.

GARY: And KLOS. I can't remember which one came first, but they all left and went to one of those two radio stations, KLOS and KMET. Never listened to 106.7 again. I got plenty frustrated watching this scene that became corporatized. Hole in the wall record stores suddenly became music chains, I began to understand about the music business: clubs, radio stations, record stores, live venues, and radio stations. Point of purchase. I wouldn't have used those words back then.

TRINA: Awful. I'm a different generation and I didn't even think we used those words even.

GARY: By 1976, 77, I did.

I had a dark room, and I would let other people use it. I think it was two different people, a friend of mine who I went to high school with, who was always ahead in music. A guy I always would sit and meet with and play records and he always seemed to kind of know what was happening. I went to dinner at his house, and he said, ‘You can't believe what's going on at the Starwood.’ I remember him saying that, and then another friend. I can't remember which came first but I do know that a friend I would loan my dark room out to, he left KROQ on and that was really it.

You always listen to the radio, or you listen to music when you're in the dark room. I went into the dark room every day. I listened to that, and I knew something was going on. This is freeform, because I'd heard it all those years, a decade earlier. This was about 11 years, but those 11 years, I got a lot older 'cause it was a big proportion of my life because I was younger. Now, 11 years is nothing. But back then, 11 years, I went from being a kid to kind of being an adult, and listening to KROQ, oh my god. It was all DJ’s and KROQ had this amazing signal. They were AM and FM; it was the same numbers as the original FM station. It had been forgotten. You know, it had been left behind. Same reason as before. You know, no one's paying attention. It's in the basement of a church. It was freeform radio again.

I had a place, because I had photography by then, and I was already in love with the city. I already knew I was on the path that I have this kind of organic chronicle of a city, that I've made this connection to a city. I'm a native here. It's a post-war baby boomer kind of chronicle I get. Now because I've been doing it so long, the people who come up to me and go, ‘You are the photographer of Los Angeles.’ You know, I am not. As a result of that, most of the calls I get are, ‘You've shot this, do you have a shot of –.’

TRINA: Oh god, they're all looking for your archives.

GARY: You know? Nope. No. Go to the LA Times. But I do shoot with a view that I am shooting Los Angeles at large. There are things that motivate me as a result of being a native here and it starts when I'm a kid. I go back to Encino when I can. I'm shooting the Valley. I’m touching on everything. At this point, I've been doing it so long. It's like every day; there's stuff that makes sense to the million stories now. I already was onto that. I knew the Olympics were coming. You've just seen, I go from Jackie [Goldberg] to…

TRINA: Yeah.

GARY: I knew what the establishment was and that the Olympics were coming. Did you ever hear of the bicentennial? The city's bicentennial was 1981.

TRINA: I was seven. It was the year the Dodgers won the World Series.

GARY: Yes. The establishment, the people who like the mayor now goes, ‘We've got the Olympics coming,’ all the people who do that were tied to a committee that was the bicentennial and the Olympics. It was this two-punch cultural happening starting in 1981, the bicentennial and the Olympics, that the city was going to celebrate culture. I knew that was happening and I would want to photograph that. I knew how the establishment talked about how they want the city celebrated and I looked at the counterculture and said, ‘They are doing it! They are absolutely doing it because all the established doors are closed. Because you have art. If you're an artist…that's why I feel like such a bad boy.

TRINA: But you're, you're making art. You're looking, you're making a comment.

GARY: So, I’m not a bad boy?

TRINA: No, you are seeing things and you're documenting, like this is really what this is. Because on the outside, it always looks like this. And especially photographs, right? You've probably been to a million of those ribbon cuttings, groundbreakings.

GARY: I love them.

TRINA: It’s interesting. It's fascinating probably to see the people and to see the types of people and what's supposed to be happening. But when you're there and you really start looking at what's going on, you see a story.

GARY: Every once in a while, I get it.

TRINA: You see something else.

GARY: [For example] He's talking to the press and she's looking at her phone. I go like this, and I go, I'm not supposed to be…I’m going to get punished.

TRINA: They should know better. They're public figures out in public doing things.

GARY: Nobody does.

TRINA: But nobody's perfect. They're people.

GARY: In all fairness, she’s not bad, but what is she going to say when she sees this photo? I'm not trying to hurt anybody but that's what got me in trouble.

TRINA: Seeing things, talking about them. Yeah, but hey, here's the counterculture. I mean, what do you think we're doing? That's what counterculture is about.

GARY: That's what I related to. This…

TRINA: …Calling bullshit.

GARY: I jumped in thinking that if these years are significant because the bicentennial is going on, because the Olympics are going on, I need to photograph this counterculture because I don’t know if this city has ever had that. I know it had the strip and there was Laurel Canyon, I know the musical history. But in the way of the counterculture that I saw in San Francisco, something that it would affect, I thought it was going to blow up because I'd seen it before. It was going to become commercialized like six months later, only because I was fooled. Establishment didn't want it. Now punk is so commercial.

TRINA: It happened.

GARY: It's so commercial. My friends, the Circle Jerks are making a living but commercial isn't the same anymore.

Circle Jerks, 2025

TRINA: Yeah.

GARY: Because there were only six stations. When it caught on, that culture, it got big because there was a common sense. It's also what's been lost. But you could also sell everybody all the same thing at the same time. There was that. Now we have, you know, the other side. I jumped in, and it was an evolution.

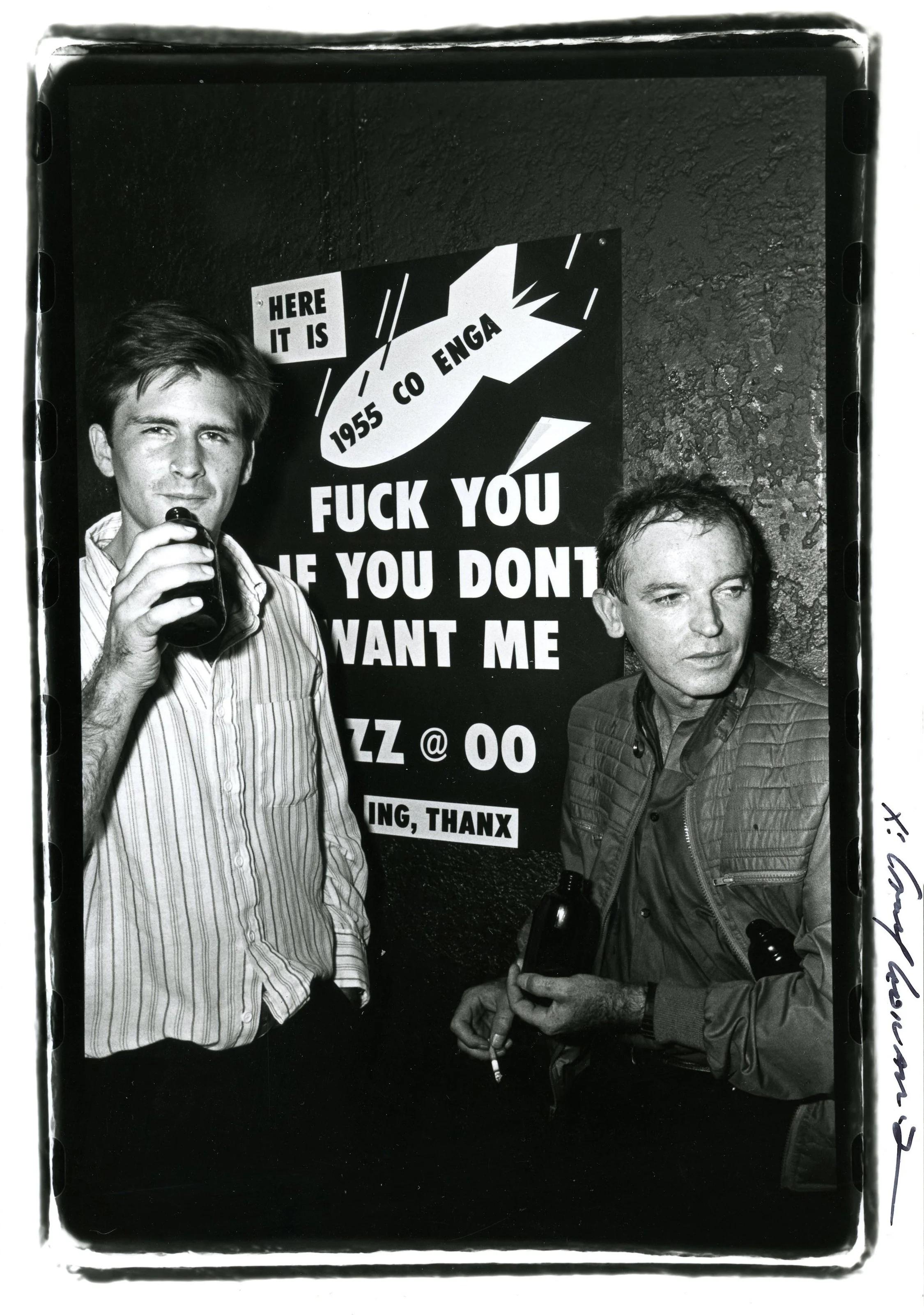

I covered it at large, didn't know anybody and I covered it at large. My first show was 1981 at a club called the Zero Zero. That was the first after after hours club. There were a number of steps along the way, but they got me to that first show. By the time I had the first show, I'd been covering the clubs. I was also putting things in the LA Weekly. Because the LA Weekly was, the one component I missed when I said there's the radio stations, there's also the media which is magazines and newspapers. That was the LA Times.

TRINA: The calendar section used to be a real calendar section. I remember growing up and as a little kid, I would get that every Sunday and cut out all the pictures and put everything on my walls and dream about going to all those concerts.

GARY: When the punk scene broke the highest, right at that time was the very beginning of free weeklies. There had never been free weeklies before. You had the LA Free Press, you had cities that had like the Village Voice in New York, but you paid for those. Probably in San Francisco, you had the San Francisco version of the Village Voice. In 1977, someone got the bright idea that we can have free weeklies, and the advertisements would give it away free. It was exactly the same time as KROQ and then you also had, have you ever heard of Zed Records? That was out in Long Beach and then you had Bomp. You had hole in the wall record stores.

I jumped in around 1978. I first began to hear this stuff and noticed that it was probably 76 and 77. Sex Pistols. Everybody heard, didn't matter who you were. When did Elvis die? Because I heard about it around the same time Elvis died. I was in Hawaii which has this weird connection to Elvis. I used to take vacation. But in 1981, I did a show at the Zero Zero. It was an after after hours club where they got the bright idea, we can buy a bunch of beer, the parties are all ending at 2:00 AM, you know, we're just getting going. They rented this place at 1955 Cahuenga. They put Carlos Guitarlos at the door. $5, all the beer you can drink until we run out.

TRINA: Amazing.

John Pochna and Mike Doud at Zero Zero

GARY: It didn't take long before all the people at all the clubs, if you were trying to monitor, you only had to go to the Zero because there was someone from everything there and you could really get that collection of what was going on. That was the beauty of the thing, it was taking people to all over the city because you couldn't play the strip. They had to be creative and there were halls out in the Crenshaw District, the Rock Corp in the Valley, and Chinatown. That was the other thing that really clued me in. Music in Chinatown, I got to go to that.

The first show was really me just going to all the different clubs I could possibly go to. When I covered, May 1980, PiL played the Olympic Auditorium, and I met people there who got me closer. It was always meeting people to get more of an insight into what was going on and what was worth listening to. I got a little deeper into it more following flyers. And someone, I was out at a club says, you want to have an art show? They got a bright idea. ‘We're running this place, the Zero Zero, it's empty all day every day, except two days on the weekend in the after hours. Why don't we show art?’ A month before, that's where I met Richard [Duardo]. I had already been to his space, in Highland Park. He put together something that also had music, that somehow invited punks in. I remember being there, but I remember meeting him at his art opening. I shot it full bore. Richard's opening with him and Bob Zoll. That was a turning point for me, connecting with the Zero.

TRINA: Nice.

GARY: My show was like March, it opened on St. Patrick's Day. Richard's must have been the month before, February, 1981.

TRINA: Wow.

GARY: Getting into the Zero, okay, I kind of randomly say this, the show that was up was a really good show. I mean, in many ways I'm not as good now.

TRINA: Oh, come on. It's different. I mean, a different time. Different shots.

GARY: Yeah.

TRINA: The energy.

GARY: There's something really great about what you do when you're, when you're young. That you can't do when --

TRINA: Supposedly we can't.

GARY: You know? A series. That's amazing.

TRINA: And you sold photographs?

GARY: Not one.

TRINA: Not one?!

GARY: No, not one, not one. I still have them. They're a lot more expensive now. If I were to sell them, I think I'd sell them together, whatever still exists.

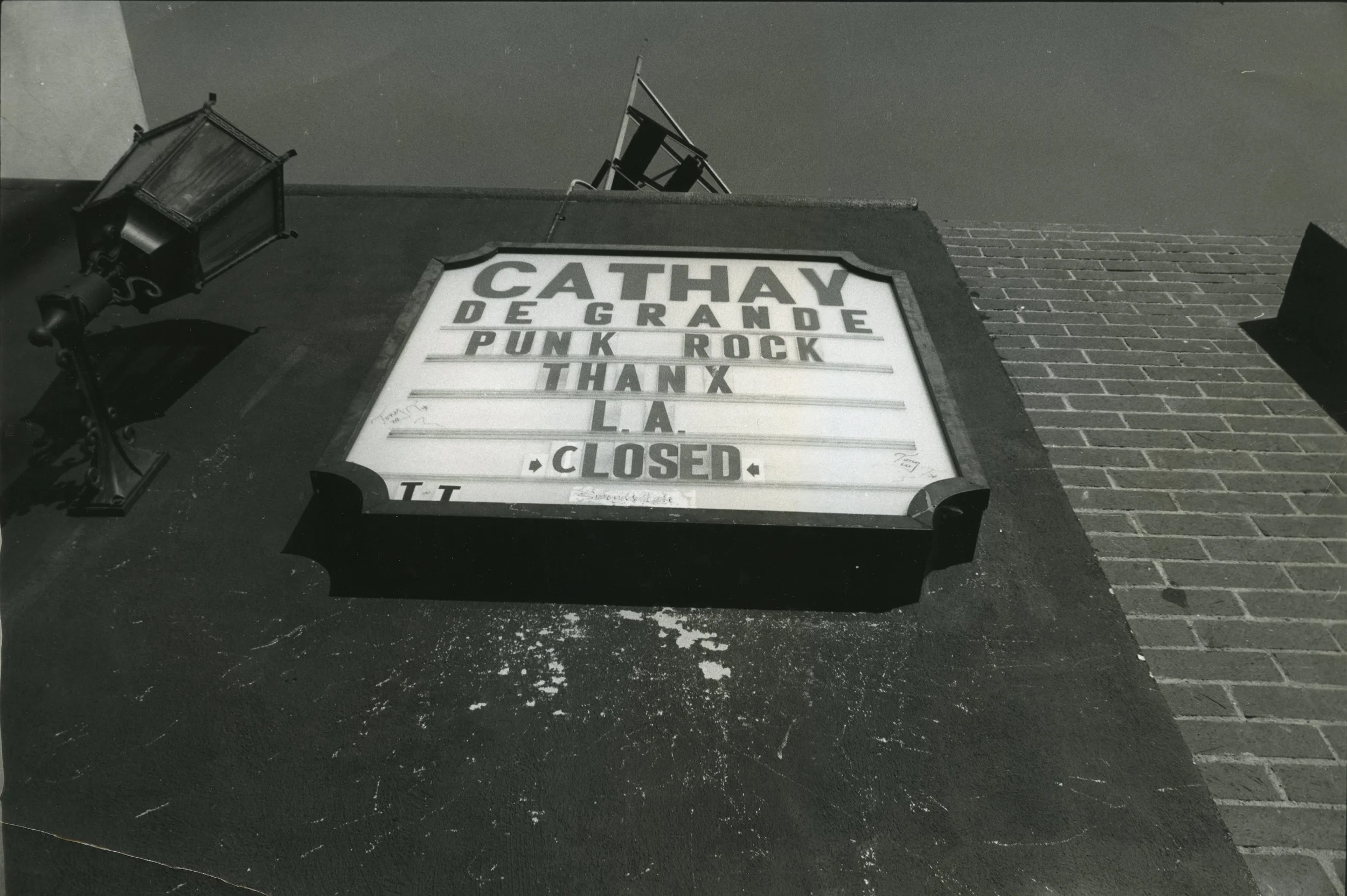

Cathay de Grande marquee, 1984

TRINA: But that's amazing. Your first show, not one sold and those were fantastic images of the scene.

GARY: And I knew they were.

It’s that thing, like showing you these pictures. I'm working for LACMA. There’s something that I’ve developed, and you’ll just get it in time. When they look at that picture of City Hall where you see the steel, most people really dig it but would have overlooked it.

TRINA: They wouldn’t have asked for that shot first.

GARY: No. It’s so funny. Did you go to the preview of the [LACMA] Geffen Galleries?

TRINA: Yes, I helped produce that.

GARY: Did I get your pic?

TRINA: I don’t know, I was running around the entire time working.

GARY: I may have your picture. Did you see on Instagram, millions of pictures of the space?

TRINA: Yes.

GARY: From every single angle. I looked at that and that's what's allowed me to take even more stock in the pictures you just saw. The guy with the safety jacket and the guy pouring concrete and the rebar that's coming up, there aren't crowds of people getting that. It's right there. It's so precious.

TRINA: It’s those moments not everyone sees - or even looks for.

GARY: It's weird (laugh) to have been there five and a half years and they had a brochure; you probably saw it, of photographs of the building. They had a foldout. You might have taken one home.

TRINA: I did.

GARY: And it said, LACMA then prominently, the name of another photographer. Prominently the name of another photographer. I looked him up and yeah, he lives in some other city and he's pretty slick. He's slicker than I am. I looked at that brochure and said, ‘This isn't as good as he normally does.’ They must have given him a weekend, flown him in. I'm looking at the light where I live with this. I live with this building and I'm looking at what they chose. I go, god, this is shit (laugh). And his name is like, you know.

TRINA: Yeah, exactly. I think they have another kind of agenda.

GARY: Now, I took a picture in June of everybody who worked on the building and the light was amazing. They have once a month, first Tuesday of every month, an all-hands meeting. That's what they call it. I’m at almost every single one. I have first Tuesday of every month they're there. It's everybody. I'm in heaven. When the light's right, it’s just magical. It's June and the light is right, and at the end of it, the superintendent says, can you, can you get a picture of us all? I'm looking around, holy shit, you couldn't gimme some notice, some warning? Can we get a ladder? I hustle around and that shot, there was a ladder and it's completely clean. That's the shot. And that's the shot for my money. That at the preview, I mean, there's the building, there's the guys who…Now I know that's romantic and poetic.

TRINA: One of the last staff meetings I was in, via zoom, Michael Govan did actually take a moment to thank the workers. But we digress…

GARY: So, I had the show at the Zero and had made a connection with the LA Weekly. I was getting feedback, you know, likes, but I was getting feedback of who was seeing what. That's when I saw people are reading the Weekly. Because they'd have a picture in the Weekly in Pleasant Gehman’s little column called L.A. Dee Da. I noticed that Carlos Guitarlos, it's interesting, was the doorman where I met him.

TRINA: Oh, really?

GARY: When I had the show at the Zero, I met Carlos Guitarlos. He worked the door. I met Top Jimmy. A lot of these people were already hanging, I'd already photographed them, Exene, and everybody. But I took a look, and I made the connection with this band called Top Jimmy and the Rhythm Pigs. They were interesting because like, Jimmy got the name Top Jimmy 'cause he worked at Top Taco and was feeding all the guys. I found out their lead guitarist worked at a print shop and he's given jobs to a million different people. I began to see a culture through this band. They seem to play all the clubs and at every club they'll be another band either headlining or opening for them. Since they were kind of starting out, they kind of found themselves and became a band at exactly that time.

The next chapter, I kind of sometimes refer to these things: ‘What's at the core of what I'm shooting.’ I called the show, I didn't want to call it punk and already these names you come up with. New Wave is probably more accurate but that carried a stigma, so I called it “Clubs and Halls” because it's what I was shooting. I was shooting clubs and halls. The next phase was Top Jimmy and the Rhythm Pigs. I got so close to them and so close to the scene through them. I moved to Echo Park. In 1979, I had a house in the Valley, got divorced, half the proceeds of the house got me the house in Echo Park.

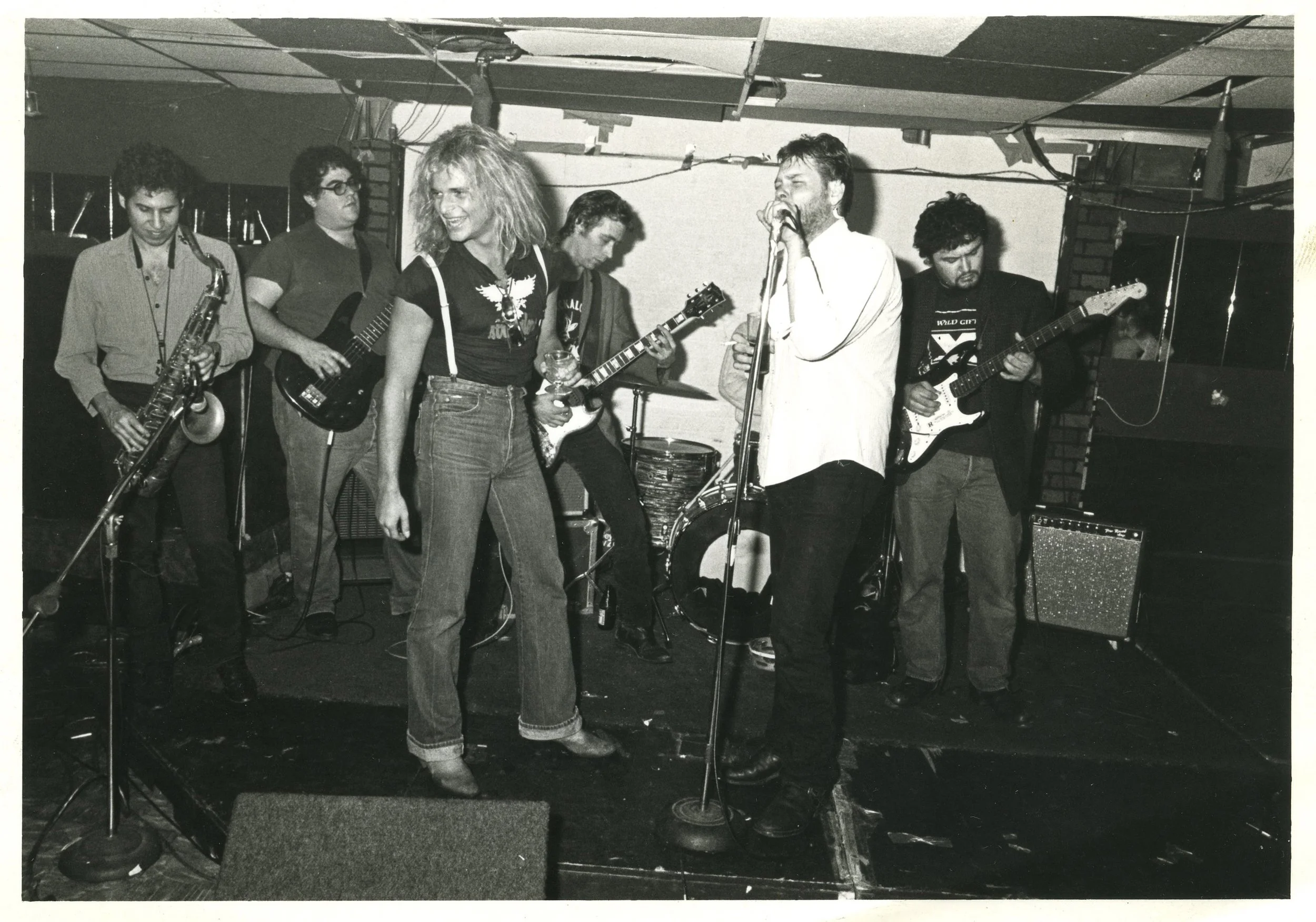

David Lee Roth meets Top Jimmy & the Rhythm Pigs at Carthay de Grande, 1981

TRINA: Nice.

GARY: Think about real estate.

TRINA: Yeah! To be able to buy a house in Echo Park in 1979, just crazy.

GARY: I owe nothing. I'm lucky because I have no mortgage payments.

I started to follow Jimmy around, and my place in the scene really came together. When I moved to Echo Park, I became almost the chief photographer at the LA Weekly. The business model I used is to be published and then people see my name out. Printing never pays. But by being known, you then get jobs that I view as grants. Since I'm photographing Los Angeles, as long as it's not in a studio, there are very few jobs I take that aren't complimentary to the overall chronicle that I'm doing. Sometimes I get paid, sometimes I don't. But I’m getting paid for LACMA.

So, people go, ‘You were like Los Angeles. You were the photographer of the scene’ and I keep going, ‘Well, it was Top Jimmy.’ Because through Top Jimmy, I'm photographing X. I was already photographing the Go-Go's, because the Weekly would ask me for photos, so you didn't see Top Jimmy per se, but it’s Top Jimmy. He's got a record coming out.

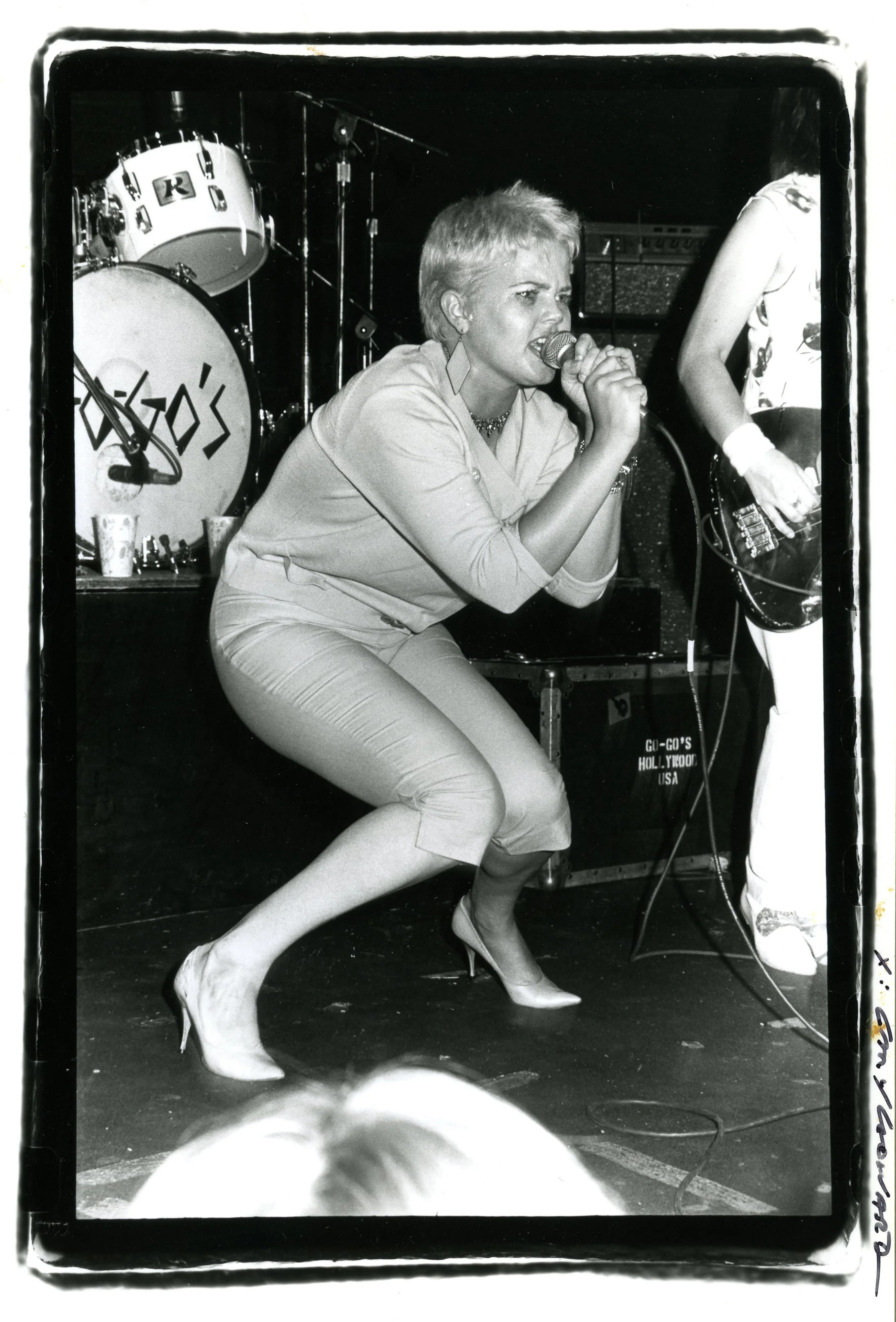

Belinda Carlisle at the Starwood, 1980

TRINA: Cool.

GARY: A reissue. He did one record.

Then there was Millie's. You know Paul Greenstein? It was his idea. Paul's from Encino. I could go on and on about Paul. Nobody knows him. He's really good at doing incredible things that become huge, and nobody knows.

It was his idea to bring music to Chinatown. He’s just this odd guy who, if I know LA, he knows everything about it. He collects wonderful stuff and knew about the scene because he's been a model, because he collects old uniforms. He also puts them on. He was a model for art students and got to know who was making a scene happen, way back in the early days. Also, he likes going places before anybody goes there. He goes there and then people go there. He discovered - you've heard of the Atomic Café?

TRINA: Yes.

GARY: Paul put the jukebox in there. Paul went to Esther Wong and said, ‘How about I bring some bands here? I'll charge admission. Your bar will pick up.’ He brought music to Chinatown. What ends up happening is, it wasn't long into it until where Esther Wong goes, ‘Why do I need you?’

TRINA: Right.

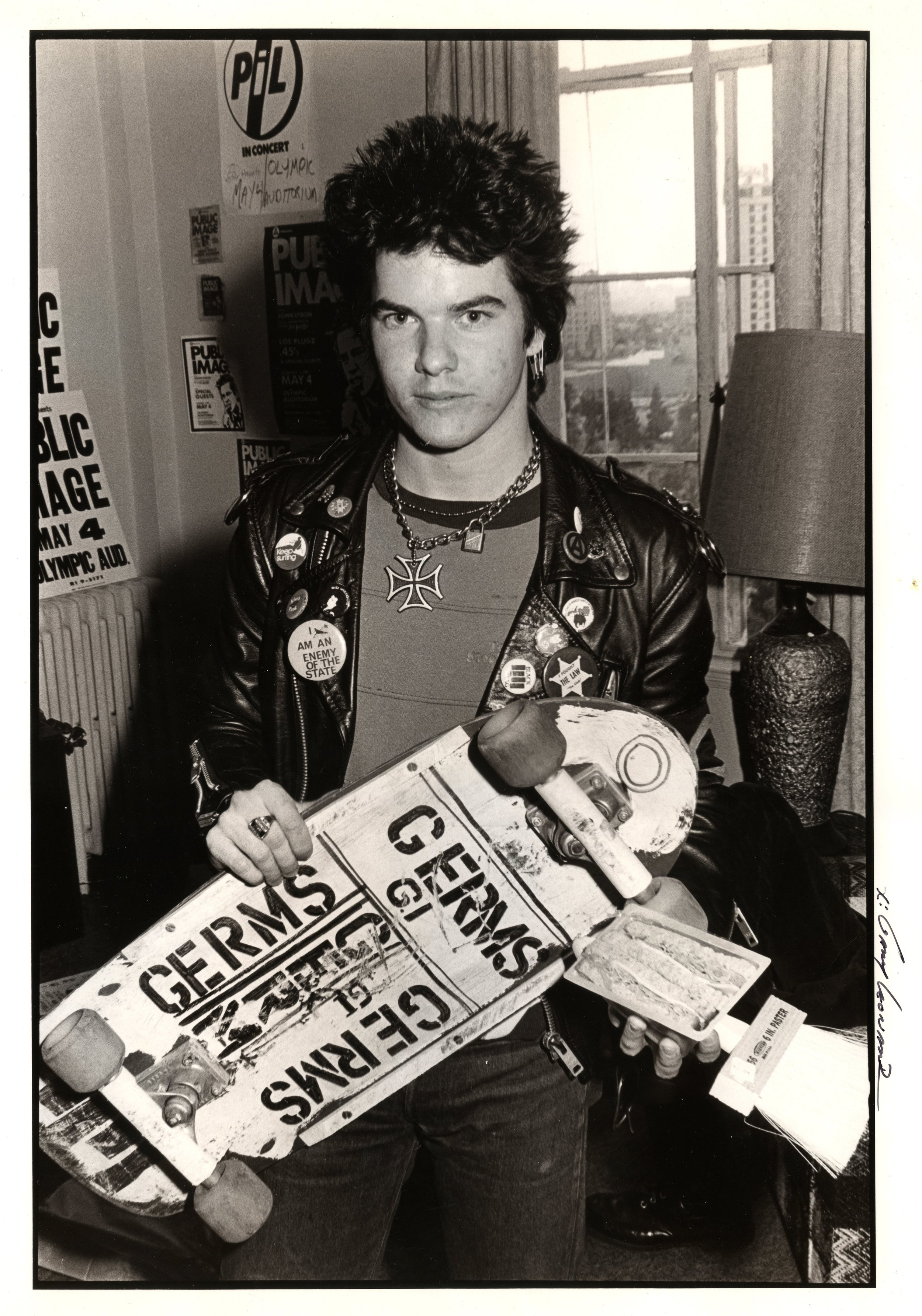

Darby Crash, 1980

GARY: You know where Millie's Diner is?

TRINA: Yes.

GARY: Okay. It was an eight-seat diner, with Millie. Paul lived a block away. I remember I was at his place, and he says, ‘Well, you should go to Millie's.’ And I go in there and everybody's like, as old as I am now. Millie is there. I don't remember it being that good. When she was ready to sell, Paul bought it. Once he bought it, because it was Paul and he was of the scene, I lived at Millie's. I said, ‘You get it.’ I'm there every single day. I was their best customer.

TRINA: That's hilarious.

GARY: And that became a chapter. There was Jimmy and the punk scene going on but I was going to Millie's every day. I was real clear that that was at the heart of everything but it was community.

TRINA: Yeah. It was community.

GARY: That's really the word. And everybody's still my friends. By the end of the eighties, I wasn't talking enough about Los Angeles. I became recognized as a music photographer. I loved the music, but I was talking about Los Angeles. I never stopped shooting the day light, but I needed to stop living at night. I continued to, because I was recognized, I did a small column, that's when I started “Take my Picture” at the L.A. Reader at the end of the eighties. There's a picture in the book of Carlos Guitarlos meeting Mayor Bradley. I took Carlos with me to cover a Hollywood star ceremony. He was living downstairs at my house. I was all in.

TRINA: Yeah, your friends become your family.

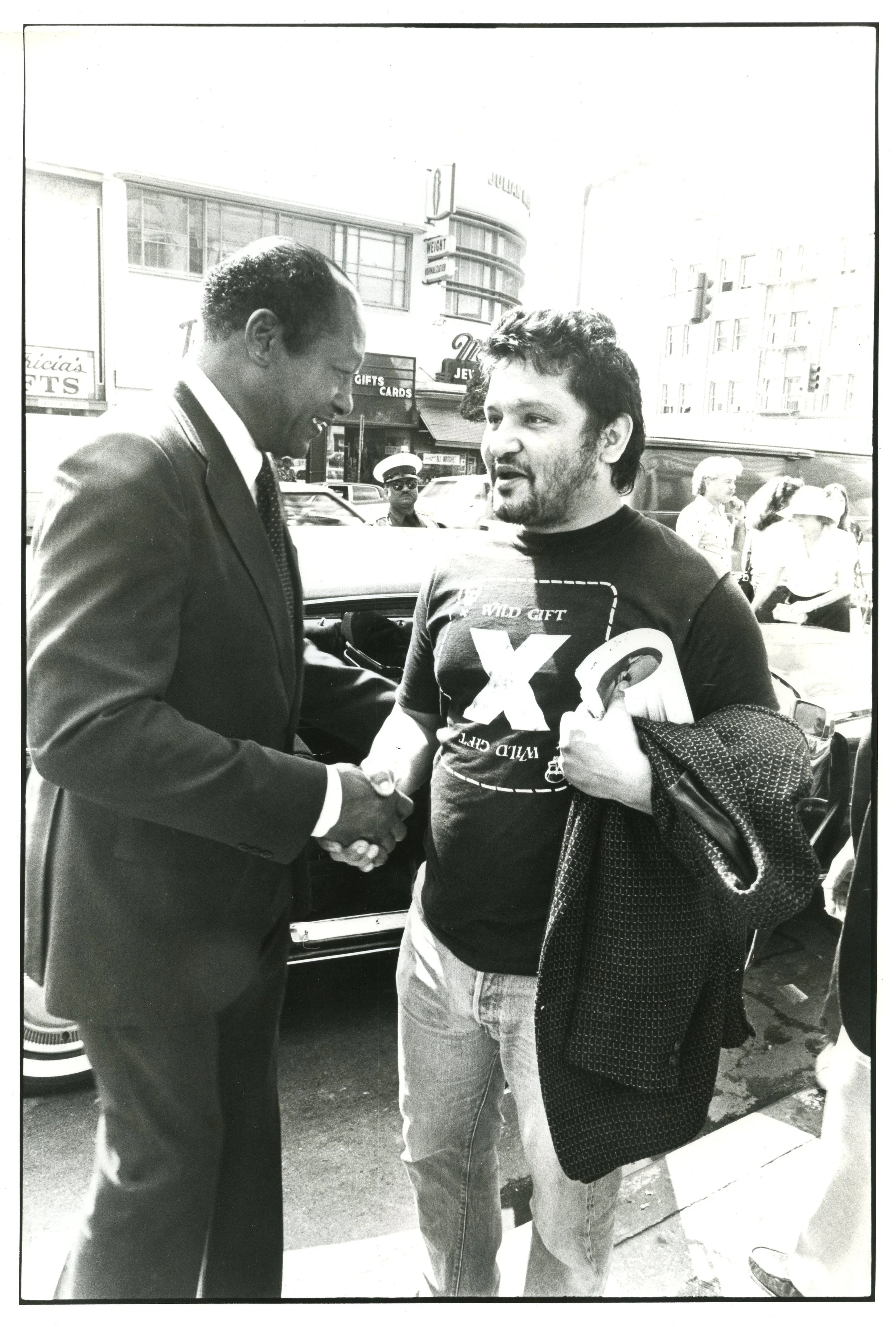

Carlos Guitarlos meets Mayor Tom Bradley

GARY: Yes. I knew that they were having a star ceremony. I said, ‘Carlos, you want to come with me?’ I'm sorry, I can't remember the name of the woman who got the star but at the very end, Carlos is kind of hanging back and I'm shooting just like Jackie Goldberg. You know, a group of people, it's a sign. I'm shooting away and I see Mayor Bradley and I'd already learned how, back at the Bruin, to shoot politicians. I said, ‘Carlos, come with me.’ I said, ‘Mayor Bradley, can I take a picture of you and a friend of mine?’ And politicians say yes to everyone. But he did a double take. He did a double take and then he remembered he was the mayor, because Carlos was Carlos.

He said, ‘Yeah,’ and I got this picture of them shaking hands, and I put it in this gossip column, LA Dee Da in the LA Weekly and it created a buzz. What the hell is Carlos doing with the mayor? It's what I wanted to do for the scene, because I saw this establishment and I saw this scene and I felt in a photo, I brought those two things together. And the fact that the mayor did a double take, but then he said, ‘Yeah,’ and the reaction it got at the Zero, because that was, holy shit, you shot Carlos. That's when the idea began, since everybody's looking at the Weekly, maybe I can begin to direct.

I remember one morning, it was always the scene, but they let me put in a picture after the Zero at sunrise I went to the Hollywood Bowl. They used to do sunrise on Easter at the Hollywood Bowl. I snuck into this counterculture this picture of the Hollywood Bowl at Easter. That's when it began to develop, this idea that I want to inform kind of everybody at the same time. That I want to do more. That really, I want to show people the city, show the establishment. There's the Circle Jerks going on, or there's the Zero Zero and show the good stuff that the city's doing. That because you're part of this group or that group, that doesn't, you know, for each side that looks at it and goes, ‘I'm not part of that because they're there and they're there.’ I’m able to walk all these different places and I'm having a great time.

TRINA: I love that. Gary. You're making me think, it's so funny about the counterculture and about how it has to be this group of people that's going against the establishment because we're being ignored essentially.

GARY: Yes.

TRINA: We're not fitting in because they're not wanting us.

GARY: That's correct.

TRINA: The truth is we all are really looking for community, and we want to fit in together. We have to figure out how to break down that division? Art and music does it. I still believe films can do that.

GARY: I don’t think I mentioned that my mom is an anti-war activist before I even cared. Vietnam began to become a thing in like 1966 and I was 18. Three years later is when you had to register for the draft and at the time, no one was looking to be drafted. If they could somehow get a different classification than what was called 1A. If you got on your draft card classification that was 1A, you were available for the draft. You would be drafted if you had that classification. Everybody was doing anything to not get classified. If you were a college student, you could get a college deferment. You were classified 2S. The classification that was most prized by everyone, which Donald Trump got, was something called a 4F. You were physically unfit. People tried to fail their physicals and people did all sorts of crazy things to prove that they were crazy. It was hard to get. In 1966, I was a gymnast. I suffered from back spasms.

TRINA: Oh, no.

GARY: Yeah. It's referred to, your back goes out. It's horrible. You can't move. However, it gets better. I got over it, and I had no problem. I was still doing gymnastics, but my mom got the bright idea to take me to build a medical history around my back, and she would take me to the doctor regularly to build up that history. At 18, you registered for the draft. My mom gave me a letter and a packet to leave with the draft board. When my draft card came, I had a 4F.

It was remarkable because I knew she was doing this, but I thought they would give me a student deferment before they would give that because I was in college. I wasn't worried about going. I was shocked that without too much trouble; I never had to worry again.

TRINA: Your mom did that?

GARY: Yes. My mother did that. She would be over 100, but she's gone. I carried that draft card with me, 70’s, 80’s, about 25 years. In 1995, I was working on a story with a writer from the downtown news and Robert McNamara. I don't know how much you know about the war in Vietnam, but he was the architect. He was the Secretary of Defense.

TRINA: Oh yeah, I know who he was.

GARY: At the time we were doing a story and he's in a bookshop, he's signing books. First, he's talking, and I'm with a writer, I suddenly remembered I've got my draft card in my wallet, so I pulled it out and he signed it. Oh my god. (Laugh) He signed a draft card that was of a draft resistor.

We bust up laughing.

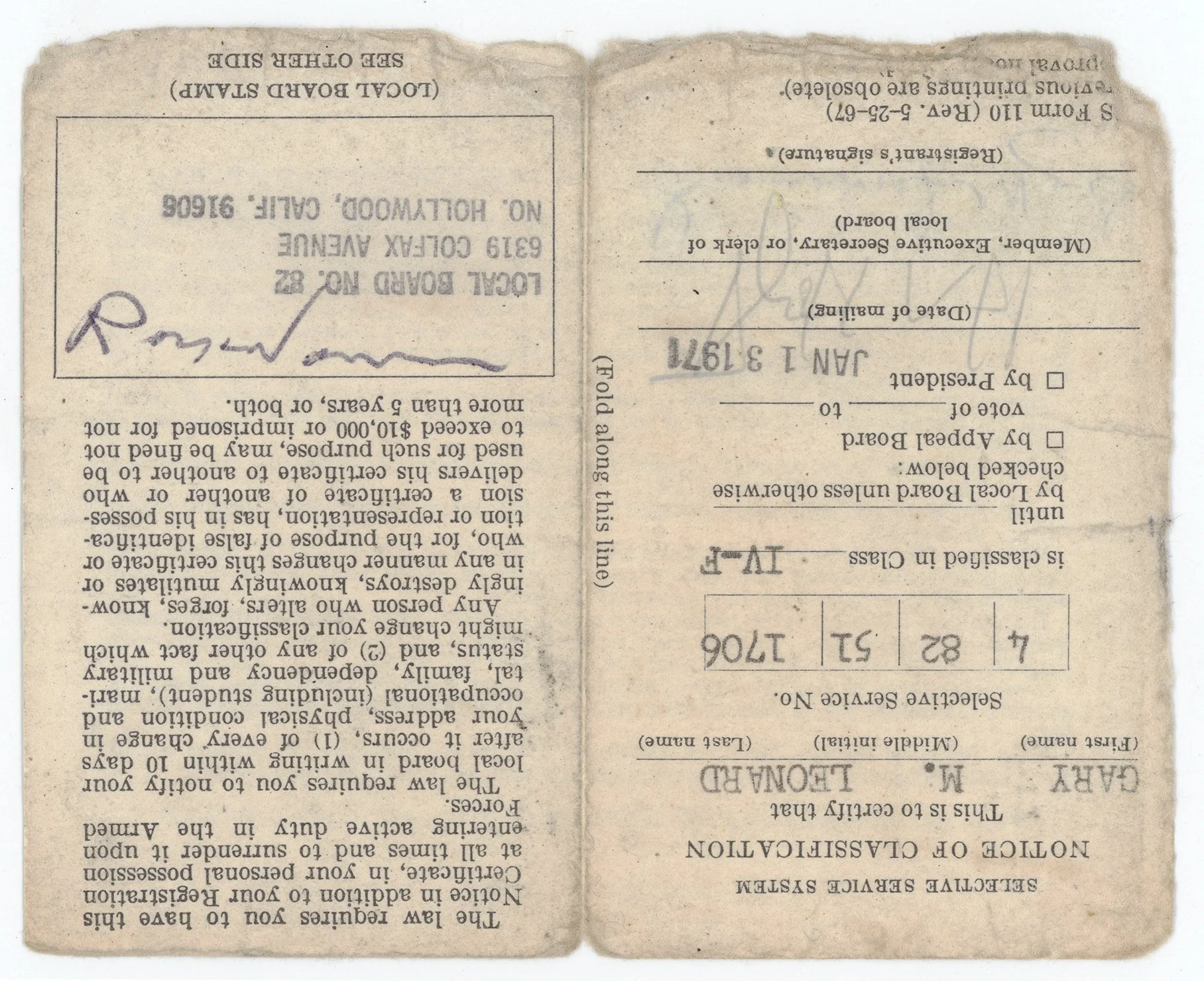

Gary’s draft card, signed by Robert McNamara

GARY: It's one of my most prize possessions. I love it. I can't remember if I pointed out that it was a 4F. I'd been taking pictures. I said, ‘Wait a minute, could you sign this?’

It's one more example…I'm not sure what the class photo is an example of, but it's a different way of looking at things.